09/23/2024

A Case for Strategic Ignorance by Design

on the power of Not Knowing

A few months back, I was getting dinner with a friend who'd just landed a big-time gig at a national regulatory body. As the food flowed, so did our conversation, and we stumbled upon a shared revelation: we'd both beaten some pretty long odds to get where we were. But here's the kicker – we succeeded precisely because we weren't supposed to.

We realized that our blissful ignorance of the barriers we faced had been our secret weapon. We didn't know we weren't supposed to make it, so we just... did. It's like we'd stumbled upon some cosmic cheat code – the adversity paradox, if you will. Sometimes, not knowing the full scope of challenges ahead can be your ticket to the impossible.

This got me thinking about a concept I've been toying with: strategic ignorance (1). Now, before you rush to close this tab, hear me out. I'm not advocating for willful blindness or anti-intellectualism. Far from it. This is about harnessing the power of a beginner's mind, about embracing what we don't know to unlock possibilities our preconceptions might otherwise obscure.

Think about it. In a world obsessed with expertise and certainty, there's something refreshingly powerful about approaching things with wide-eyed wonder. The Japanese have a term for this – "Shoshin," (2) which translates as ‘beginner’s mind’ and refers to the paradox: the more you know about a subject, the more likely you are to close your mind to further learning. As the Zen monk Shunryu Suzuki put it in his book Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970): ‘In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.’

It's about cultivating an attitude of openness and lack of preconceptions (3), even when you're knee-deep in a field.

An independent, uninfluenced, disinfected cognitive approach

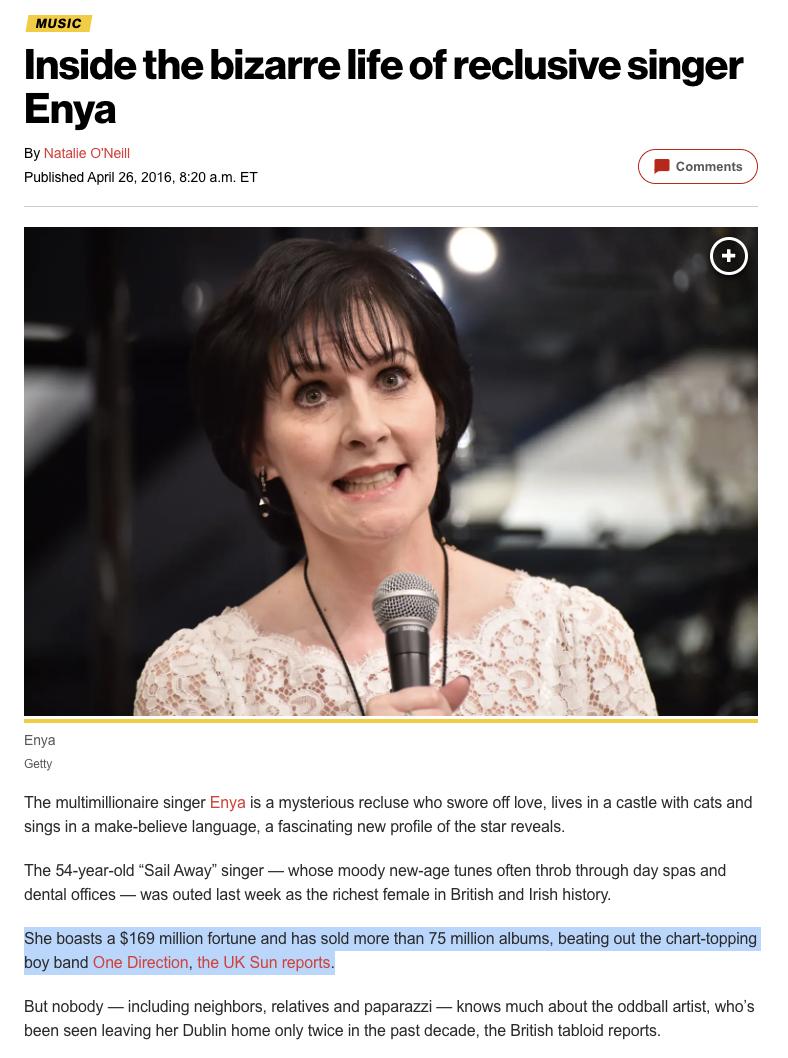

Take Enya, for instance. Yes, the Irish singer-songwriter with the ethereal voice. Instead of schmoozing with other artists and soaking up external influences, she holes up in her Victorian mansion, refusing to listen to anyone else's music. It's like she's created her own bubble of strategic ignorance, allowing her to craft sounds that are uniquely, well, Enya.

There's a reason we talk about "beginner's luck." Newbies aren't weighed down by the pressure of past achievements or the fear of failure. They're free to experiment, to fail spectacularly, and to stumble upon solutions that experts might overlook. It's what author George Leonard calls "the spirit of the fool" – essential for true learning and innovation.

Now, I'm not suggesting we all become hermits or willfully ignore valuable knowledge. But what if we approached more situations with the mindset of a beginner? What if, instead of always seeking to know more, we sometimes embraced not knowing? (4)

What if we let things unfold (5)?

The paradox of knowledge

In our quest for success, we often cling to the belief that more knowledge is always better. But sometimes, knowing too much about the obstacles ahead can be paralyzing. It's the adversity paradox in action – our ignorance becomes our superpower, giving us the audacity to attempt the seemingly impossible.

Strategic ignorance isn't about remaining uninformed. It's about maintaining a flexible, open mindset that allows for innovation, risk-taking, and personal growth. It's about being willing to venture into the unknown, to ask the "dumb" questions, to challenge assumptions – including our own.

In a world that often values expertise above all else, maybe it's time we recognize the power of strategic ignorance. Sometimes not knowing what's possible is the very thing that makes the impossible achievable.

Why do adversity paradox, beginner's mind, shoshin work? Can we manufacture a cognitive reset?

But here's the million-dollar question: Why do the adversity paradox, beginner's mind, and shoshin actually work? And can we somehow bottle this cognitive magic?

Our brains are wired to take shortcuts, building mental models based on past experiences. Usually, this serves us well, but these models can also trap us in rigid thinking patterns, blinding us to new possibilities. That's where strategic ignorance comes in, acting like a cognitive reset button.

When we embrace not knowing, we're telling our brains, "Hey, forget what you think you know for a sec." This mental decluttering opens up space for fresh perspectives and unconventional solutions. It's like clearing your cache and restarting your mental browser – suddenly, everything loads a bit differently.

The adversity paradox works by short-circuiting our tendency to self-limit. When we don't know something's "impossible," we don't waste energy convincing ourselves we can't do it. We just... do it. It's the cognitive equivalent of those stories where someone lifts a car to save a trapped child – when we're unaware of our supposed limitations, we're capable of extraordinary things.

So, can we manufacture this cognitive reset? I think we can, and it doesn't require a complete memory wipe (sorry, Eternal Sunshine fans). Here are a few tricks I've found helpful:

The "Five-Year-Old Method": Approach a problem as if you're explaining it to a curious five-year-old. This forces you to break down complex ideas and question your assumptions.

The "Martian Anthropologist": Imagine you're an alien studying human behavior for the first time. How would you interpret the situation without any cultural context?

The "Skill Swap": Try tackling a problem using tools from a completely unrelated field. What would a chef's approach to coding look like? How might a poet strategize a business plan?

The "Constraint Curveball": Impose an arbitrary constraint on your problem-solving. How would you do this with only $5? What if you had to do it underwater?

These exercises aren't about ignoring valuable knowledge or experience. They're about temporarily setting aside our mental models to see what new insights might emerge. It's a way of tricking our brains into that "beginner's mind" state, even when we're neck-deep in expertise.

Is this any different from first principles thinking?

"Isn't this just first principles thinking with a fancy new name?" I think there's definitely some overlap. But strategic ignorance is like first principles thinking's wild cousin – it takes things a step further.

First principles thinking breaks down complex problems into their most basic elements and reasons up from there. It's powerful, no doubt. Elon Musk famously used it to revolutionize space travel and electric cars. But it still operates within the realm of what we know, using existing knowledge more effectively.

Strategic ignorance, on the other hand, ventures into the realm of what we don't know – and embraces it. It's not just about breaking down problems, but about approaching them as if you've never seen them before. It's about cultivating a mindset that's comfortable with uncertainty and open to possibilities that might not fit into our existing frameworks.

Think of it this way: first principles thinking is like disassembling a car to understand how it works and then building a better one. Strategic ignorance is like forgetting what a car is altogether and asking, "What's the most efficient way to get from point A to point B?" You might end up reinventing the wheel, or you might invent teleportation.

The key difference lies in the attitude towards knowledge itself. First principles thinking seeks to use knowledge more effectively. Strategic ignorance temporarily sets knowledge aside to make room for new perspectives. It's not about ignoring facts, but about being willing to question everything – including our own expertise.

A tool for life

This is why strategic ignorance is powerful beyond just problem-solving or innovation. It's a tool for personal growth, empathy, and creativity. It allows us to step outside our own experiences and see the world through fresh eyes. It's what allows a seasoned chef to be inspired by a child's simple sandwich creation, or a veteran teacher to learn something new from a first-year student.

In the end, strategic ignorance isn't about staying ignorant. It's about cultivating the ability to toggle between knowing and not-knowing, between expertise and curiosity. It's about maintaining the flexibility to see old problems with new eyes, to question our assumptions, and to approach challenges with the unencumbered enthusiasm of a beginner.

Notes:

It's crucial to note that "strategic ignorance" as used in this essay does not refer to willfully ignoring negative consequences or unethical behavior after the fact. Rather, it is about proactively cultivating a beginner's mind, not retrospectively choosing to ignore information.

A poem on Shoshin.

I wrote an essay on cultivating conceptual change through cognitive conflict, which requires proactive interference.

I wrote a tweet about the most challenging yet rewarding asset being an independent, uninfluenced, disinfected cognitive approach to the self and to the world.

Christopher Alexander has written a ton about “unfolding.” Unfolding is the process of learning what something should be by working on it.

Here's Mark Zuckerberg, the poster child for 'strategic ignorance' in tech. Dropped out of Harvard, didn't know jack about running a global company, and built Facebook anyway. Sometimes, not knowing the rulebook lets you rewrite it entirely.

His motto: “move fast and break things”