04/10/23

The Ramanujan Theory of Genius

obsession vs. devotion, an iteration on Paul Graham’s bus ticket theory

There are two essays that inspired today’s piece: Paul Graham’s The Bus Ticket Theory of Genius and Kristin Posehn’s Unpacking the Mystery of Ramanujan’s Dreams.

I aim to iterate on Graham’s bus ticket theory with one of my own – The Ramanujan Theory.

In his essay, Graham reasons the secret ingredient to becoming an eminent figure in your field beyond the obvious talent and diligence – obsession. He suggests a recipe for genius, the bus ticket theory: to have a disinterested obsession with something that matters. In other words, an impartial fixation on a subject of significance.

He uses the example of an obsessed bus ticket collector, someone who has passion, but their passion is pointless. I agree with the recipe, except for one word. I don’t think it’s obsession, but rather devotion, perhaps a disinterested devotion.

Obsession runs out. It wanes and trembles in the face of reality.

True devotion is a choice you make to give yourself to something, and that means giving all of yourself. Not just the self that always feels like showing up. It means giving the part of yourself that’s grumpy, unsure, full of doubt, and tired. It means offering yourself with all your imperfections.

True devotion finds a way through obstacles and the ebb of energy. Toku

In contrast with the bus ticket collector, Graham uses all-time genius, Ramanujan to illustrate obsession that matters. Srinivasa Ramanujan was an Indian mathematician, a self-taught genius who made remarkable discoveries in mathematics despite having no formal training in the subject. One could say that he was obsessed.

I searched for dictionary definitions of the two words in trying to understand why I felt differently about them. Obsession is intrusive. Devotion is enthusiastic. Geniuses failed their experiments all the time. Their devotion to their subject(s) made them show up again and again with enthusiasm and loyalty. Obsession emanates discomfort. They were at ease. They were present. They felt the fullness of all their subjects, whether that be physics, or alchemy, or theology (Einstein 😉). They didn’t obsess. They followed their curiosity.

Perhaps it’s the connotation to the words, and I don’t think it’s semantics. Connotation refers to the emotional or cultural associations that a word carries, while semantics is the study of meaning in language. While connotation is an aspect of semantics, semantics encompasses a broader examination of meaning, including both denotation (literal meaning) and connotation. So, while connotation is a part of semantics, the two terms are not exactly synonymous.

The two concepts – obsession and devotion– are often used interchangeably. But are fundamentally different. They also feel fundamentally different. Obsession is negative, it feels like an all-consuming force that can be harmful or unhealthy, driven by fear, insecurity, or a need for control. Devotion is positive and an uplifting force that can lead to a life of fulfillment and purpose – a feeling of strong loyalty or dedication toward something, characterized by a willingness to make sacrifices or to work hard. A deep commitment to a subject brings meaning and purpose. It is rooted in love, respect, and a sense of duty. It radiates transcendence.

Now Graham does consider this, the willingness to make sacrifices. Drawing a parallel between the bus ticket theory and Carlyle’s acclaimed definition of genius as an “infinite capacity for taking pains,” he contends that the capability for painstaking effort equates diligence. However, I contend that Carlyle implied devotion.

It is the underlying motivation that makes the two words different. Not to confuse motivation with intention, I agree with Graham that these geniuses did not intend to “lay the groundwork” for their future discoveries. They did it because they liked it. Because they were devoted to the process, not the outcome. They were pulled toward it because they respected it. Feeling disinterest and respect for something at the same time are not mutually exclusive. A disinterested devotion.

Posehn’s essay offers a poignant depiction of Ramanujan’s devotion:

After reading first-hand descriptions of Ramanujan from his friends and colleagues, the one word mentioned over and over again is devotion.

Perched on a step outside his parent’s house or hiding underneath a cot, he worked on his slate board day and night for years. His work was certainly not all intuitive flights—his notebooks were filled with a strange mixture of finished results seemingly plucked from the ether, and unrelated pages of relentless numerical calculation, in which he got to know each positive integer as a “personal friend.”

As the scholar B. M. Wilson put it, Ramanujan’s research into number theory was often “preceded by a table of numerical results, carried usually to a length from which most of us would shirk.” Outside of math, in his smallest acts he scrupulously observed his family’s religious customs, regularly invoking the goddess Namagiri and basing his actions on what he took to be her will. For purely religious reasons, he refused Hardy’s initial, life-changing offer to math it up in England, and only relented after Namagiri blessed the invitation in one of his mother’s dreams. Traditions he could not observe due to social pressure at Cambridge, such as the tuft of hair customarily worn by Hindu men, caused him genuine pain.

Ramanujan was devoted.

Devotion is desire transmuted across time into love. It is an elevation of attention; a singleness of purpose, but in service to something greater than ourselves. Ramanujan’s pure devotion to god and to math seem indistinguishable, in both the hints and anecdotes that remain as a record of his life, and especially in his dreams.

Posehn’s essay triggered this revelation. It’s not obsession. It’s devotion.

I propose a refinement: Devotion to something that matters.

Graham’s bus ticket theory also suggests that you slow down when you get older. He says

“Perhaps the reason people have fewer new ideas as they get older is not simply because they're losing their edge … you can no longer mess about with irresponsible projects the way you could when you were young and no one cared what you did”

“..people are less likely to do great work after they have children. Here interest has to compete not just with external obstacles, but with another interest, and one that for most people is extremely powerful.”

.. implying a negative correlation between aging and the likelihood of achieving genius status. Here’s what I have to say. Ramanujan, Darwin, Einstein were devoted. So were Churchill, Kahneman, and (Albert) Claude – who won their Nobel prizes at 79, 68, and 75 respectively. Sometimes it’s a juicy slow burn. And “what others think”, or “being cringe” as my generation would call it, doesn’t matter when the motivation is out of respect, when you are committed to the process of transcendence. When you’re devoted to something greater than yourself.

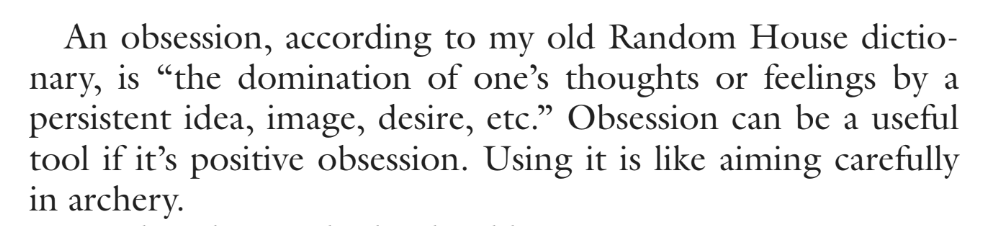

Or as Octavia Butler might say –– Positive Obsession.

Passage from Octavia Butler’s essay “Positive Obsession”

From Octavia Butler’s Journal Entries.

positively obsessed with Octavia’s journal entries (framed) + all my unhung art

Thanks to my friends Avi Sharma and Maaria Shah for supporting me throughout the writing process of this essay.

This piece is 10/50 of my 50 days of learning. Subscribe to hear about new posts.